Understand emotional mismatch to better support people through change

Introduction

When he was a young man, my dad trained to be a battlefield medic.

He told me that they would show the trainees video of gruesome injuries and war trauma. The purpose, supposedly, was to prepare them for the horrors they would see on deployment.

He said that there were three reactions: people did nothing, people cried, or people laughed.

He told me that the ones that did nothing were the ones the trainers were most worried about screening because the assumption was that they were not processing their emotions. He wasn't sure about the scientific basis for this approach, but it was many years ago.

I found the people laughing to be the most peculiar. My dad assured me that they found what they were seeing just as disturbing as everyone else, but they couldn't express it in a way we might consider rational. It was like their wires got crossed between the feeling and the expression.

How do we make sense of the feelings others have, and work to ease their change journey when it is so easy for our visible cues to be so mismatched to the actual feelings?

As change leaders, we must account for this mismatch when responding to stakeholders. Doing so will require that we understand how that mismatched display of emotions happens, and then develop some alternative tools to explore their interactions.

Understanding the Mismatch

I recently read Malcolm Gladwell's book Talking to Strangers. While critics contend that Gladwell argues for the certainty of ideas and concepts where there is no consensus, I find that his books are always thought-provoking. He is also an excellent storyteller, something all change leaders can learn from.

Talking to Strangers explores the challenges we face trying to understand others. Gladwell leads with an idea that I find fascinating for those charged with understanding people and leading change: the mismatch of emotions and their visual cues.

This is where someone's emotional reactions —what you might call their tells— differ from what we expect. Their eyes don't knit in a frown when upset, their mouth doesn't hang open when surprised, or they laugh when watching horrific violence.

We expect people should respond in a prescribed way to a situation. When they don't, we assume we understand their inner-response based on their outer-reaction. Gladwell makes a fascinating case for this assumption being both wrong and dangerous.

US psychologist Paul Ekman conducted influential research in the 1960s and 70s that suggested people's facial movements in response to emotions were universal across cultures.

But recently, as summarized in this Nature article, scientists have been using more sophisticated imaging and research messages. This data found patterns that suggest that facial reactions happening in the moment are not as clear, or not universal.

Our inability to consistently read emotions on people's faces is matched by the inability of our language to capture emotion in words.

Our incomplete language of emotion

One can learn a lot about a culture by its language. One fascinating phenomenon is that some cultures have words for emotions that others do not share. "Schadenfreude", the German word for finding joy in the suffering of others, is a common example.

It is an entire emotion that the other languages (including English) did not find the time to name, so we had to borrow it. There are many, many examples of this.

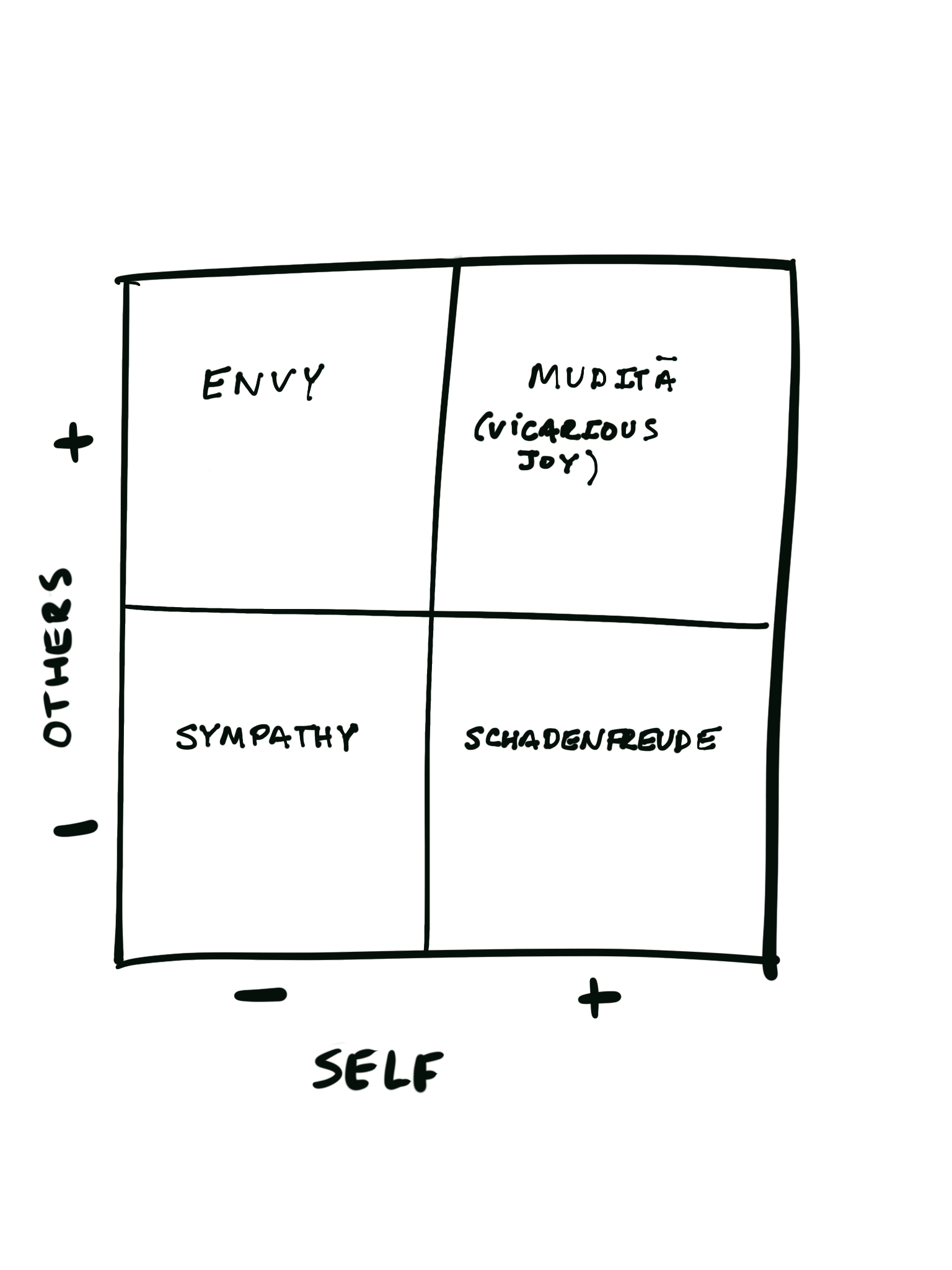

Let's take schadenfreude and picture a grid: one axis covers our own feelings of happiness and sadness, and the other axis covers another's happiness and sadness.

We have a word for sadness at others suffering (sympathy) and words for feeling bad about someone's joy (envy), but we didn't (in English) have a word for feeling joy for someone's misfortune. We needed to borrow that from our German neighbors like a cup of sugar (or more apt, salt.)

We also seemingly lacked a word for the joy at someone else's joy. There is pride, but that does not quite capture it. The Buddhists have that word: it's Muditā.

How can we pretend to read emotions on a person's face when we can't even read them in text for lack of an actual word?

This concept raises so many questions about how we see ourselves and the role of language in framing how we talk about emotion.

Without a word to serve as a cognitive marker for our understanding of what is going on with someone else, it is very hard to react to it in an empathetic or appropriate way.

Now, mix that same lack of signaling that comes from missing a word to missing a non-verbal cue. Our ability to understand and respond plummets.

The mismatch and the wall

The mismatch is a real barrier to understanding, especially in groups that don't know each other well.

Consider an HR professional delivering hard news to a colleague. Maybe it's a layoff or a furlough. That HR staffer may be trying to project calm to make the process less painful. They may be feeling sympathy for the employee being affected, but not wanting to prompt an emotional release in them that could make the matters worse.

What the employee sees is something different. It could be cold, or distant. Maybe the HR person, in an effort to calm themselves, has a forced smile. That can seem sadistic to someone in pain.

Our inability to communicate our real alignment in feelings or values can shove a wall between people that becomes hard to scale. This wall can easily blockade your change efforts without drawing notice.

In leading change we have different goals and tactics to accomplish them. When we don't have a solid understanding of the emotional state underlying the people we are working with, it's easy to lean too heavily on the tells from their facial expressions and body language. We've seen those tells can be deceiving.

Often, our audience doesn't know how they feel about something at first. Yet we expect that we know enough about them through small facial movements and muscle contractions to make conclusions about how to proceed. That can force us down a path of reactions prematurely.

One way to prevent this is to engage with our audience in a more substantive assessment than reading their face. Ask exploratory questions beyond "how are you feeling?" Building a shared conversation establishes guideposts that make understanding possible.

The world of emotional cue mismatch is a sufficiently well-researched area to warrant study for change practitioners. What are our people actually feeling when they face a change? How can we relate to them in a way that will actually make progress?

There are other tools available to us that can help with this challenging process.

Photo by Ryan Franco on Unsplash

A more accurate measure of change and alignment

Our goal should be to understand how people will respond to a change, and what resources or support they need to overcome the barriers to that change.

Emotions are a major variable in the change effort, but we need to find a better indicator for those feelings than facial cues and body language (which we seek subconsciously and extensively.)

But we have an alternative: action is an excellent indicator of response, better than words and better than body language.

Imagine someone, maybe a senior leader, telling you that they support your change effort. You're excited by their endorsement, and ask them to send a communication. You even draft if for their review.

It never goes out.

Perhaps that person didn't recognize how little they supported your effort, but it was less than the cost of one mouse click.

That's the challenge of the mismatch. Their body language, their words —everything— suggested support you needed. But the action didn't back that up.

Their follow-through told you everything. You need to do more work with this person.

When leading change, being able to come up with insights into the level of support and guidance you are getting from people is a powerful tool because it allows you to focus your efforts and identify areas of progress or support

Conclusion

We should rely less on what we think our people feel, and more on what they do as a measure of how they are adopting change.

By having exploratory conversations and doing our best to build shared understanding, we have a real opportunity to avoid the mismatch and find empathy.

Along with monitoring action over our guess of people's feelings, we can make better adjustments to our change plans and hopefully be more responsive to the needs of our people.